Conflicts and controversies surrounding the future of agriculture are popping up everywhere. As agriculture has emerged as a major cause of the climate and ecological crisis following fossil fuels, extreme measures such as closing farms have emerged in the Netherlands, deepening conflicts between the government and farmers. Controversy is also growing in New Zealand and other countries as they are regulating greenhouse gases in the agricultural sector.

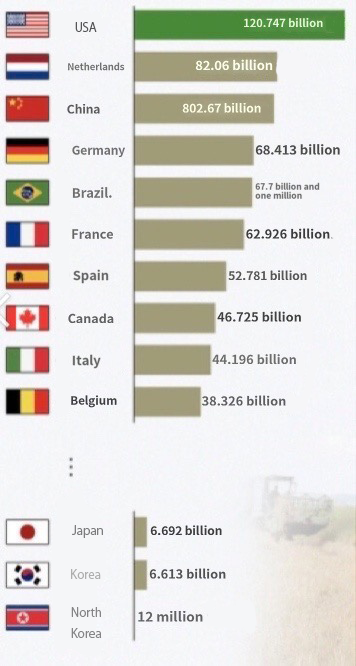

In Africa, which is facing an agricultural crisis due to soaring chemical fertilizer prices, it is pointed out that it is urgent to start “alternative agriculture” that will not repeat other countries’ mistakes.The most extreme country in which conflicts over agriculture are expressed is the Netherlands, a European agricultural and livestock export power. At the end of last month, the Dutch government decided to buy and close 3,000 farms to reduce ammonia and nitrogen oxides, which are considered environmental pollution and warming-inducing substances, and decided to receive applications for voluntary closure by the end of the year. The government plans to force the purchase of farms from next year if the applicant falls short of the target. According to the Dutch National Statistical Office, 51,042 farms are in operation in the Netherlands as of November. 6% of all farms are in a situation where they are closed.The Dutch government has brought about the closure of farms because nitrogen emissions must be cut in half by 2030 under the European Union’s natural protection regulations. The government believes that the total number of livestock in livestock farms will have to be reduced by 30 percent to realize this goal. The number of cows, pigs, and chickens raised by Dutch farmers amounts to 112.68 million, more than six times the population (17.77 million). The Netherlands ranks first in Europe in the number of livestock per unit area.Although the country is only (41,865 square kilometers), thanks to its intensive livestock industry and agricultural advancement, it ranks second in the world in agricultural exports after the United States. According to data from the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), the Netherlands’ agricultural exports reached $82.06 billion in 2019, 68% of the world’s No. 1 U.S. (120.74 billion dollars). The largest exports were fruits and vegetables ($22.659 billion), meat and processed products ($11.283 billion), dairy products and eggs ($9.467 billion) are also major exports. Agriculture is an economically important industry in the Netherlands.At the same time, the peasant issue is also a politically sensitive issue. Because of that, the Dutch government has been reluctant to regulate agriculture. As a result, the Netherlands’ largest nature conservation area, Theho Hebelüber National Park, faced a serious biodiversity crisis, broke the nutritional balance of the ecosystem and even caused snail shells to not form properly, according to a recent report.

Farmers are strongly protesting, saying, “No farms, no food.” Farmers’ opposition began in earnest after the administrative court ruled in May 2019 that the government’s nitrogen policy violated EU regulations, and the government began restricting the size of livestock breeding. However, the government officially announced plans to purchase and close farms in June. Farmers immediately staged violent protests across the country, and recently showed signs of taking action again. Bart Koiman, a farmer who raises 120 cows in Hazersbauder, southwestern Netherlands, said, “We don’t want to set fire and block the road, but if we do nothing, it’s all over. We will be kicked out of the ground.” “Farmers are being treated as criminals,” said Caroline van der Plas, head of the “Farmers’ Citizens’ Movement” (BBB), a political party created during farmers’ protests. “Everything they do is said to be wrong,” he criticized.Agricultural regulations for environmental conservation are not unique to the Netherlands. According to the international statistical site Our World in Data, 18.4% of global greenhouse gas emissions in 2020 occurred in the process of agriculture, forestry, and land use. This is the second largest after the energy sector (73.2%). For this reason, countries around the world are turning to agricultural regulations following fossil fuel regulations.The New Zealand government has also decided to impose taxes on greenhouse gas emissions in the agricultural sector since 2025, and countries are regulating agriculture. a cattle farm in Oxford, New Zealand

The New Zealand government plans to impose taxes on methane, carbon, and nitrous oxide emissions in the agricultural sector for the first time in the world from 2025. When Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern announced the plan last October, farmers immediately protested. “We don’t want a country that can only plant pine trees and grow food,” said Bryce Mackenzie, a farmer who organized the opposition movement. “We want future food security.” Ireland also plans to reduce greenhouse gas emissions in the agricultural sector by 25 percent by 2030, while Denmark has set a goal of reducing gas emissions in agriculture and forestry by up to 65 percent. For this reason, conflicts over agricultural regulations are expected to emerge as an issue in many countries after next year.

Danusi Dinesi, founder of the Dutch agricultural think tank “Clim-Eat,” pointed out that the biggest problem with climate change measures in the agricultural sector is that farmers are excluded from the policy-making process. “Climate policy should be pursued in a much more gradual and comprehensive way,” he said. “The key to the solution is how to participate more farmers and reflect their needs.”The need for eco-friendly agriculture is also being raised in Africa, where intensive agriculture, which relies on pesticides and fertilizers, is relatively less prevalent. Germany’s hunger-fighting movement and research group INKOTA recently released a report analyzing the problem of agriculture relying on chemical fertilizers (“golden bullets or bad choices?”) claiming that chemical fertilizers are at the center of the global food crisis. The report pointed out that chemical fertilizer prices have risen much more than energy and agricultural prices since the COVID-19 pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, causing a serious agricultural crisis in Africa and other countries. According to data from the International Monetary Fund (IMF), when the price was set at 100, international fertilizer prices as of October were 304.7, up much more than energy (259.9) and food (134.8). The report warned that they are aiming for the last remaining unexplored Africa amid deepening monopolization of the global fertilizer industry, with four major companies, Nutrien (Canada), Yara (Norway), “CF Industries” and Mosaic (U.S.), producing 33% of the world’s nitrogen fertilizer.Farmers are harvesting rice in Mozambique, Africa. In Africa, there is also a movement to convert to eco-friendly agriculture along with soaring chemical fertilizer prices. The report called for attention to organic fertilizers spreading in Tanzania and Ghana. Tanzania’s organic fertilizer producer Amin Zakaria said that farmers who use organic fertilizers are not only reducing fertilizer costs, but also increasing soil fertility, improving nutrients in crops, and improving the taste of agricultural products. Audrey D’Arco, founder of Ghana’s organic fertilizer company Savon Sake, said the country’s farmers had similar effects, and many of the farmers facing soaring chemical fertilizer prices were anxiously looking for alternatives. In line with this trend, the Senegalese government launched a support plan in November last year to inject 10% of agricultural subsidies into organic fertilizer production.Some say that switching to environmentally friendly agriculture could lead to a food crisis, but there is also a strong objection that it is an exaggerated concern. Dutch think tank Klimit Dinesh said, “The reality is that one-third of the world’s food is simply discarded every year,” adding, “We can solve the problem by improving the production system to reduce food loss and strengthening land and agricultural water management.” Natasha Urlemans, head of food and agriculture at the World Wide Fund (WWF) Netherlands, pointed out that if farmers change their view of nature as an alliance, they will find clues to solve the ecological and agricultural crisis.