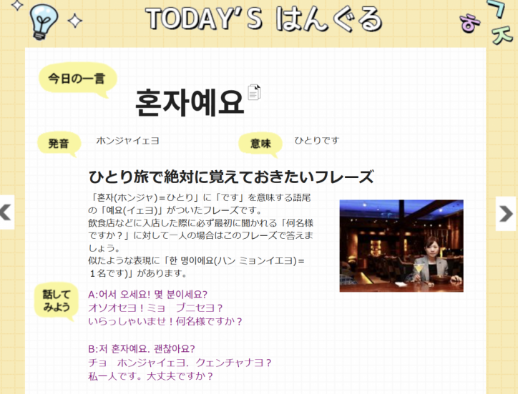

Japanese online media and social networking services (SNS) have recently been sharing “useful tips for traveling alone in Korea.” Japanese instructors who teach Korean often emphasize a practical phrase for use in Korea: “I’m alone.”

This is because eating or drinking alone—known as honbap (solo dining) and honsul (solo drinking)—still carries a certain social stigma in Korea. Popular dishes such as budae jjigae (army stew), grilled pork belly (samgyeopsal), and dakgalbi are often difficult to order for just one person. As a result, solo travelers are advised to clearly state that they are dining alone when entering a restaurant.

The rise in single-person households, driven by low birth rates and rapid population aging, is a shared phenomenon in both Korea and Japan. According to “Single-Person Households in Statistics 2025,” released by Korea’s National Statistical Office on January 9, Korea now has 8.04 million single-person households, accounting for 36.1% of all households.

In Japan, data from the 2024 National Survey of Family Income and Expenditure conducted by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare shows that single-person households make up 34.6% of the total. In 2019, the figures stood at 30.2% in Korea and 26.9% in Japan, highlighting how rapidly this trend has accelerated in both countries.

While Korea has only recently surpassed 8 million single-person households, Japan has more than twice that number—approximately 19 million people living alone. As of 2023, Japan had 18.995 million single-person households, nearly half of which (46%) consisted of individuals aged 65 or older.

For Japan’s single-person households, the challenges extend beyond solo dining and drinking to include issues such as funerals, inheritance, and end-of-life planning. The number of people living alone in Japan is expected to continue rising, with the National Institute of Population and Social Security Research projecting that single-person households will account for 44.3% of all households by 2050.

Despite similar levels of average monthly spending—1.69 million won in Korea and 169,000 yen in Japan—the lifestyles and social perceptions of people living alone differ markedly between the two countries.

According to a nationwide survey conducted by McDonald’s Korea and Gallup Korea involving 1,034 adults, 70% of Korean respondents said they preferred eating with others rather than dining alone.

In contrast, a survey conducted last year by Japanese market research firm Cross Marketing among 2,500 men and women aged 20 to 69 found that the most common response (42%) to the question “Have you ever felt a barrier to dining alone?” was “No.” Dishes perceived as less comfortable for solo dining included yakiniku (Japanese barbecue), hot pot or shabu-shabu, and buffet meals. However, even these categories saw a 4–6 percentage point decline in resistance compared with the 2022 survey.

When asked about the image of people who eat alone, 45% of Japanese respondents said they had “no particular image,” making it the most common answer. This was followed by “They seem free and enviable” (22%). Negative perceptions accounted for only 10%. Cross Marketing interpreted these results as showing that “overall resistance and psychological barriers to solo dining have significantly diminished.”

One major reason for this difference in perception is the development of services tailored to single-person households in Japan. Across Japan’s B2C (business-to-consumer) market, an increasing number of restaurant chains now offer counter seating or tables specifically designed for solo customers. Retailers are also shifting away from bulk products in favor of smaller portions and single-serving packages as the default. In the home appliance market, refrigerators with capacities under 200 liters now make up the largest share.

There is also growing interest in understanding single-person households not merely as consumers, but as a distinct lifestyle. Japanese real estate company Able operates a dedicated research unit called the Hitorigurashi Kenkyusho (Living Alone Research Institute), which regularly studies changes in housing, consumption, and leisure patterns among people living alone.

Public–private collaboration is also expanding. In October last year, the Japan Research Institute established a research group focused on end-of-life preparation services for elderly individuals living alone, bringing together multiple companies in a cooperative framework. The related market is estimated to be worth around 1 trillion yen.

Japanese media widely view the single-person household sector as a future “blue ocean” market. The Nikkei notes that “as the number of single-person households continues to rise, demand for related services is surging, creating abundant opportunities for private-sector businesses.”

JULIE KIM

US ASIA JOURNAL